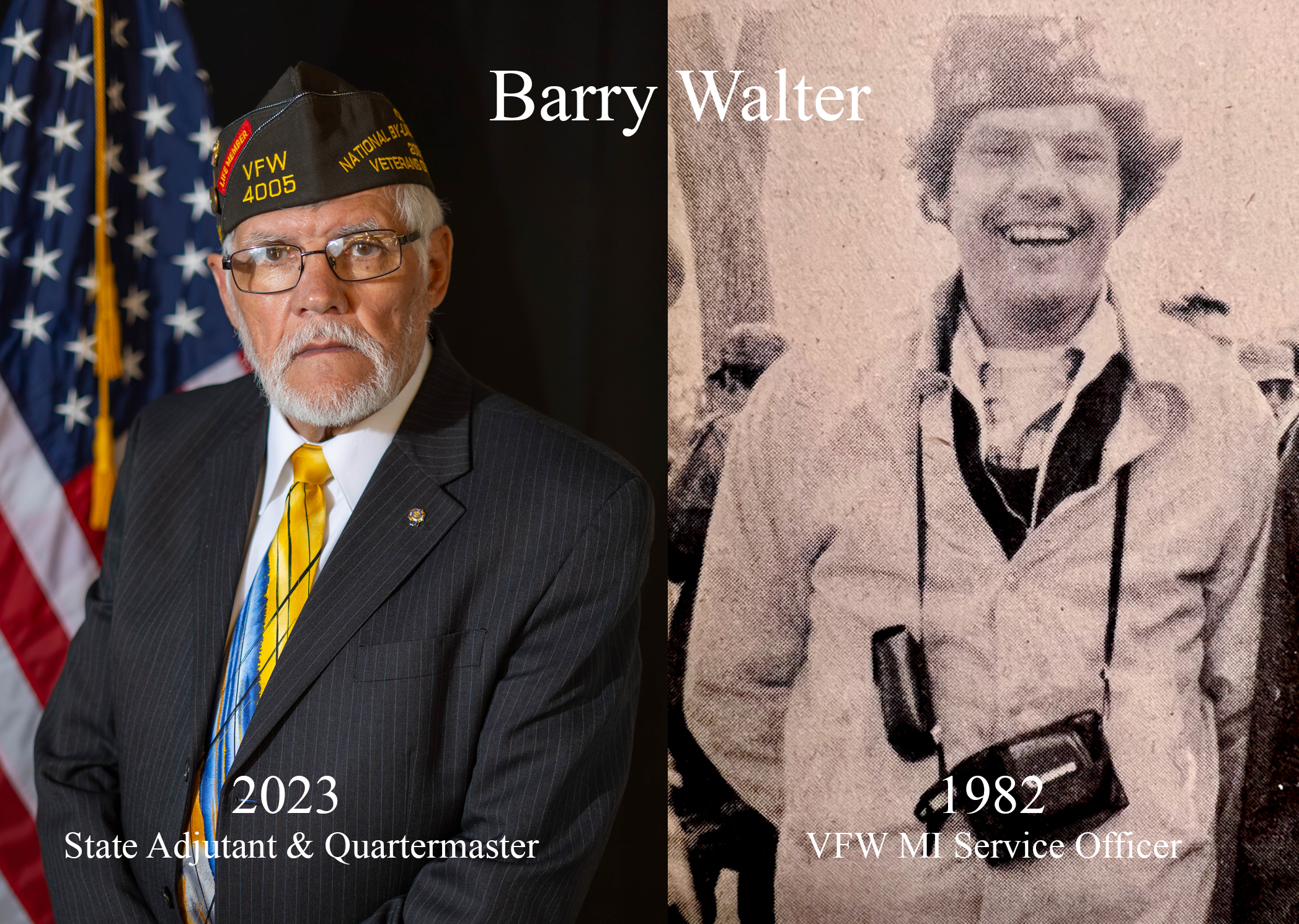

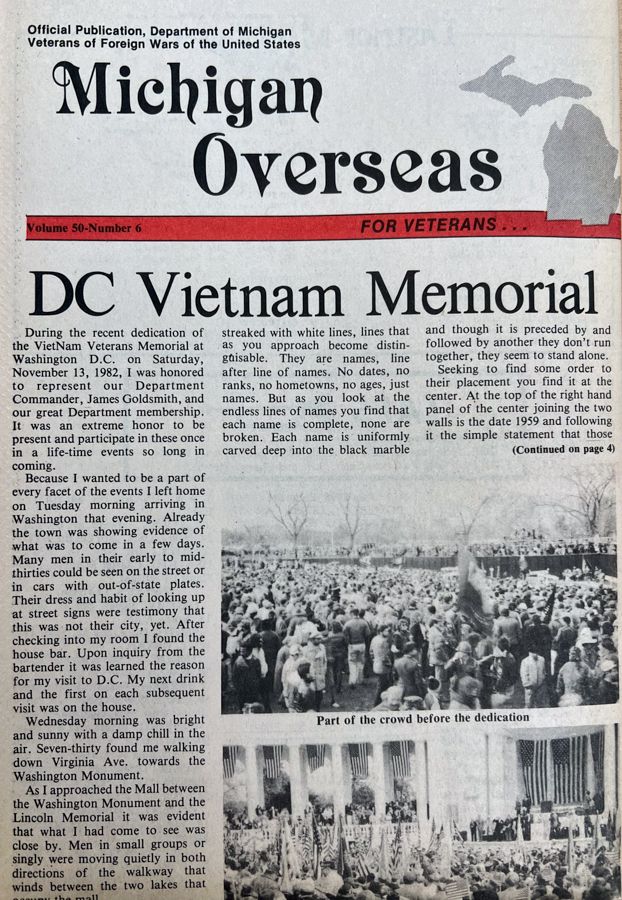

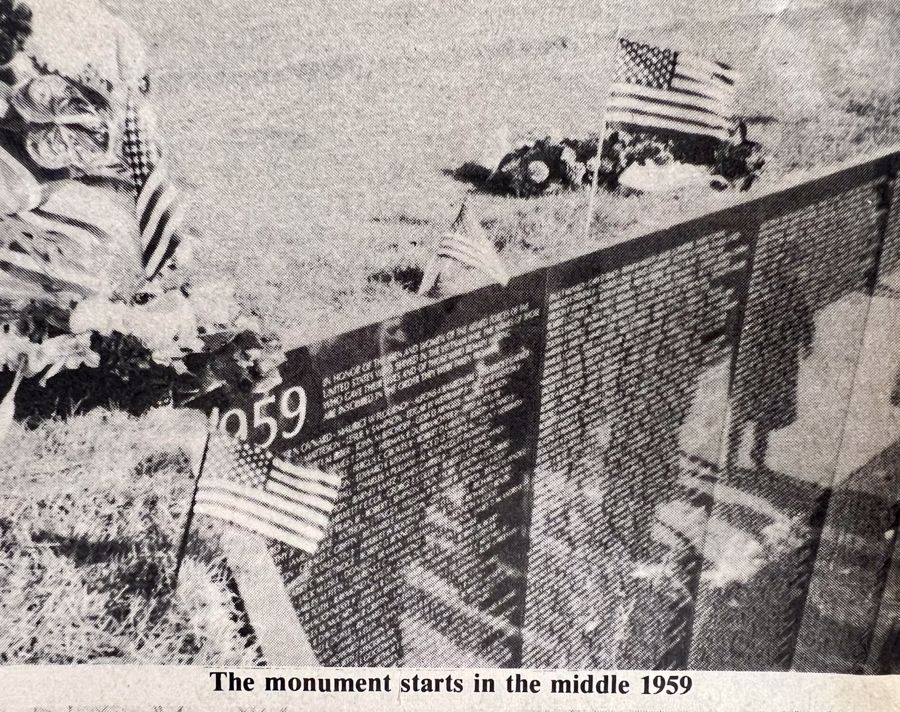

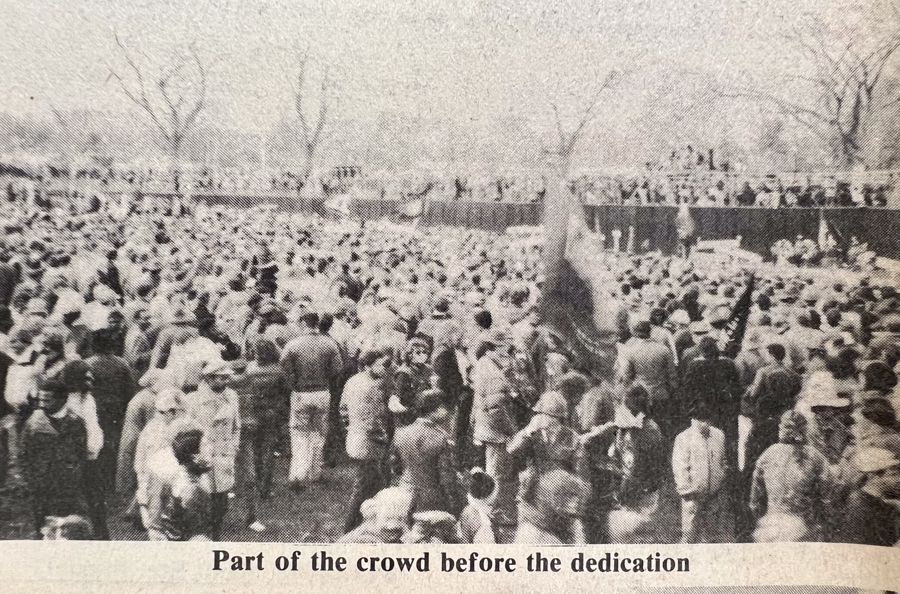

VFW Department of Michigan Adjutant & Quartermaster Barry Walter attended the Washington D.C. Vietnam Memorial Dedication on November 13, 1982. Barry served in the U.S. Army, and was deployed to Vietnam for 47 months between 1967-1971. Now, 76, Barry recalls being a 35-year-old VFW service officer, witnessing history for his generation of warriors. The following is an article he wrote about this experience published in the VFW Michigan Overseas Veteran Newspaper in December 1982 Volume 50-Number 6. At the time of this article, the National Vietnam Memorial held 57,939 names of Americans who died in the Vietnam War. Today, the 200-foot long wall holds more than 58,000 names. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------- During the recent dedication of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial at Washington D.C. on Saturday November 13, 1982, I was honored to represent our Department Commander, James Goldsmith, and our great Department membership. It was an extreme honor to be present and participate in these once in a lifetime events so long in coming. Because I wanted to be a part of every facet of the events I left home on Tuesday morning arriving in Washington that evening. Already the town was showing evidence of what was to come in a few days. Many men in their early to mid-thirties could be seen on the street or in cars with out-of-state plates. Their dress and habit of looking up at street signs were testimony that this was not their city, yet. After checking into my room I found the house bar. Coupons inquiry from the bartender it was learned the reason for my visit to D.C. My next drink and the first on each subsequent visit was on the house. Wednesday morning was bright and sunny with a damp chill in the air. Seven-thirty found me walking down Virginia Ave. towards the Washington Monument. As I approached the Mall between the Washington Monument and the Lincoln Memorial it was evident that what I had come to see was close by. Men in small groups or singly were moving quietly in both directions of the walkway that winds between the two lakes that occupy the mall Many showed signs of having slept outside all night, unshaven faces, carried sleeping bags and the ever present camera. Walking along that walkway, passing men wearing bits and pieces of faded jungle fatigues, you avoided their eyes as they avoided yours. The path of tears was still visible on some and you got the first real premonition of what was to come. Pass the refreshment stand not yet open, up the hill with the Lincoln Memorial in view through the trees and just off to the right over the edge of the hill it stood. The first view is a sliver of black. As you leave the walkway and top the crest of the hill, The Monument’s walls themselves are below ground level and as a result you don’t get the feeling of walking up to it. Rather, you walk down and into it. It draws you. Some are drawn to the ends, thinking to start at the beginning. Some are drawn to the center, to the walls that rise over ten feet tall. Those that are drawn to the center find here is the beginning and the end, the first and the last. As you walk down the hill the reflective black walls become streaked with white lines, lines that as you approach become distinguishable. They are names, line after line of names. No dates, no ranks, no hometowns, no ages, just names. But as you look at the endless lines of names you find that each name is complete, none are broken. Each name is uniformly carved deep into the black marble and though it is preceded by and followed by another they don’t run together, they seem to stand alone. Seeking to find another order to their placement you find it at the center. At the top right hand panel of the center joining the two walls is the date 1959 and following it the simple statement that those named on these walls are listed in the order in which they were taken from us. From there the names seem unending as the wall stretches up the hill to the right. From the left the black wall rises up out of the tailored lawn again bringing forth those names, all those names. Finally the list comes to an end. It's 1975 and it's the end. The quiet here in the center is shatterproof. Even at this early hour visitors mill around but you hear nothing. Every person's thoughts are self contained as they search the names. They look for a name, sometimes more than one name. All the names are there. It is devastating. The scene is repeated all weekend and into the next week. Men, alone or in groups, couples searching along the walls. Finding a name, they hesitate, reach out and touch the edges of the letters, as if trying to get inside the stone. Parents, brothers, sisters, friends of men who died so long ago reach out and touch their Nation’s Monument to their sacrifice. At the foot of the walls flowers appear, sometimes a single stem, sometimes a wreath, sometimes with a picture of a young man in uniform fresh from basic training. All those names. 57,939 names. Wednesday was a very lonely day. Wednesday night I went to the National Cathedral for the beginning of the candlelight vigil, which would result in the reading around the clock for over two days of the names of all those killed or missing in America’s longest war. Names read by volunteers one at a time in the quiet chapel. Once in a while a cry is heard and then it is stifled as another name is read. Thursday is Veterans Day in 1982 and I went to Arlington Cemetery for the traditional services. The services at Arlington are beautiful. They are precise and dignified, full of music, flags, crisp orders and clicking heels. A stranger sitting next to me offers the information that last year there were no crowds and wonders where did they all come from this year. Maybe it was because of that Memorial. Yes, I said, maybe it was. Thursday and Friday were spent in meeting old friends and making new ones. Impromptu reunions took place everywhere. Each of the hotels was aswarm with former GIs looking for and finding buddies or guys who knew guys. Units opened hospitality rooms and the beer flowed. Some of these rooms stayed in operation almost nonstop from Wednesday to Sunday morning. Friday evening the National VFW office sponsored a beer bust with hotdogs and beans. It was attended by about two thousand guys and we all drank a lot of beer. The VFW got a good shot in the arm that day. On Saturday morning it seemed as if every jungle fatigue and boony hat that survived Vietnam was on Constitution Ave. Thousands and thousands of guys who had never marched in a parade except graduation from basic training were here to march in this one parade, this parade for them. Each state gathered behind their own banner. As we marched down the street and the crowd yelled their welcome it didn’t matter how much or how few we were because we were here. Other vets joined us from the crowd as we passed. Michigan was well represented in this parade. The Nitehawks, who led the parade, came back and marched again with us. At the end some of us fell back to march again with our Division. It was a parade to remember. A parade of guys who came home, come together to honor those who had not. The memorial dedication itself was almost anticlimactic. The program was traditional. The exception was the remarks by the National President of Gold Star Mothers, the mother of a Vietnam casualty. Her message was short, from the heart and to your gut. Everyone within ten feet of me was in tears and I still don’t know who followed her on the program. It was a beautiful program for the dedication of a monument symbolic of everything our country has to offer the future, the same resource this country has offered too many times in the past, our young men. It was the dedication of a number, 57,939. A number reduced to names on black marble walls. This was a dedication of a monument to end all such dedications, let there be no more cause to send young men to strange places only to have their names appear on endless walls of black marble. On Sunday morning the National Cathedral was filled with ex-GIs paying their last respects while the hotels tried to clean up before the next convention. The services were solemn and meaningful but afterwards it seemed as if most held another private service, at the monument. It was a magnet that drew you back, back for one last looked before you could leave this place so far away. The weekend was an emotional experience that brought back to life all the memories of friends made and lost in a time when days were marked on the side of your helmet. Even on Tuesday morning when the out-of-towners had left, the memory of those events pulled you back to the monument. It pulled me back to look at the four lines it took to list the names from that day in May 1970. Or the lone name that reached out to me from just above eye level, the sun reflected off the wall just like it reflected off the plexiglass of his helicopter on May 25, 1971. This is the memorial that stands for all of us, what we were and what we are. This memorial reduces all the speeches of glory and battles won or lost to one common denominator, the names of those lost on muddy hillsides mindless of the ultimate victory. It is simply the roll call of those that died, 57,939. And may they forever know that we miss them. Photos and article by Barry Walter, 1982

FOLLOW US